Here

is a

list of our ongoing projects! To learn more about each one, simply

click on a link to expand the project description.

PAC@VSS

We enjoy presenting our research and getting feedback at

the annual Vision Sciences

Society conferences. Now you, too, can enjoy our abstracts and posters

from the comfort of your desk!

PAC@VSS: 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009

Current Projects

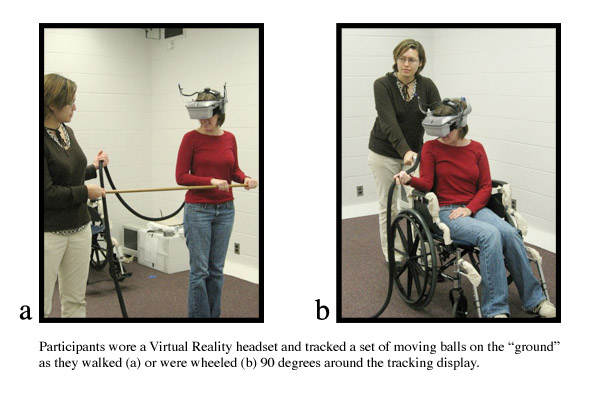

How does self-movement affect multiple object tracking?

Investigations of multiple object tracking aim to further our understanding of how people perform common activities such as driving in traffic. However, tracking tasks in the laboratory have overlooked a crucial component of much real-world object tracking: self-motion. We investigated the hypothesis that keeping track of one's own movement impairs the ability to keep track of other moving objects. Participants attempted to track multiple targets while either moving around the tracking area or remaining in a fixed location. Participants' tracking performance was impaired when they moved to a new location during tracking, even when they were passively moved and when they did not see a shift in viewpoint. Self-motion impaired multiple object tracking in both an immersive virtual environment and a real-world analog, but did not interfere with a difficult non-spatial tracking task. These results suggest that people use a common mechanism to track changes both to the location of moving objects around them and to keep track of their own location.

Related Publications: Thomas, L. E., & Seiffert, A. E. (2011). How many objects are you worth? Quantification of the self-motion load on multiple object tracking. Frontiers in Psychology. [ link ]

Thomas, L. & Seiffert, A. E. (2010). Self-motion impairs multiple object tracking. Cognition. [ link ]

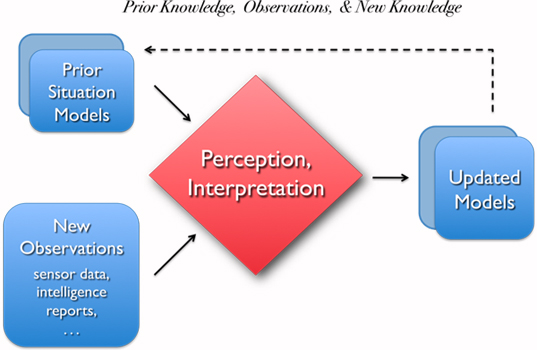

How do people decide what information is salient?

DSR #22703 STTR Research Project: This collaboration between Vanderbilt University computer scientists and cognitive scientists will work with DiscernTek analysts to create a a system of human-computer interfaces for application to military command or business that represents human perception and cognition for the purpose of providing ready access to salient information.

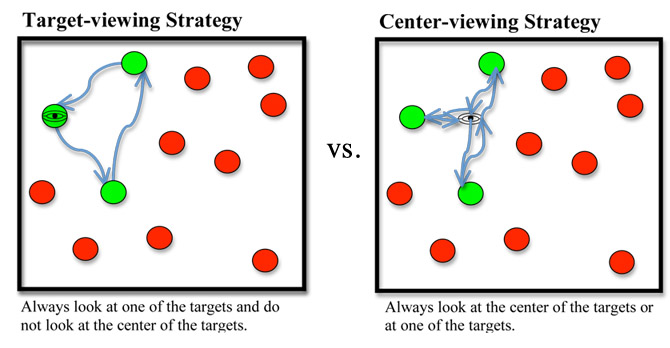

Where do people look during multiple object tracking, and why?

Multiple object tracking measures the ability to covertly attend to multiple locations over time. Previously we demonstrated that participants tracking multiple targets often look at the center of the target group (Fehd & Seiffert, 2008), a strategy we label "center-looking". This is intriguing because participants are not always looking directly at targets or saccading between them, a strategy we label "target-looking". The current experiments investigated whether people engage in center-looking only when target-looking is too difficult.

Participants tracked targets moving randomly amidst distractors while we measured the amount of time they viewed the targets or the center of the targets. To increase the demand for foveation and hence increase target-looking, a series of 3 experiments manipulated dot size (from 0.3 to 0.06 degrees visual angle), dot speeds (from 2 to 24 degrees per second), and target motion (similar or dissimilar). These experiments tested a range of difficulties, pushing participants to their perceptual limits. Results show that center-looking persists regardless of the ease with which targets can be foveated. Center-looking is not the default alternative to target-looking, but instead may reflect a different cognitive process. It seems that the time spent looking away from targets is not determined by the difficulty of looking at them

Related Publications: Fehd, H. M. & Seiffert, A. E. (2010). Looking at the center of the targets helps multiple object tracking. Journal of Vision, 10(4). [ link ]

Fehd, H. M. & Seiffert, A. E. (2008). Eye movements during multiple object tracking: Where do participants look? Cognition, 108(1), 201-209. [ link ]

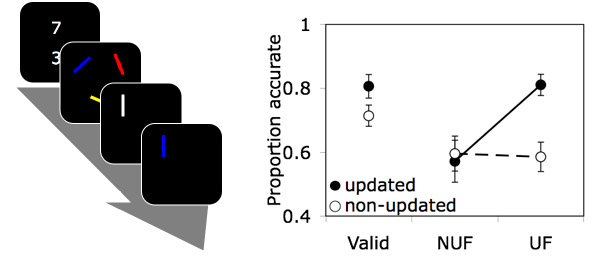

Updating objects in visual short-term memory

Previous work has suggested that updating memory is constrained by properties of attention (Oberauer, 2002). Visual attention is object-based (Scholl, 2001), as is the storage of information in visual short-term memory (VSTM; Luck & Vogel, 1997). We investigated whether updating VSTM is also object-based by determining whether effects of updating one feature of an object would spread to its non-updated features. Results showed that the facilitative effect of updating was specific to the updated feature of an object, and did not spread to its non-updated features. This feature-selective effect suggests that updating VSTM is not object-based (Experiment 1), even though storage was object-based (Experiment 2). Control experiments ruled out strategy- (Experiment 3) and stimulus-related (Experiments 4 & 5) accounts of the data. These findings indicate that updating VSTM does not exhibit all properties of attention and support an account of independent feature representation in VSTM (Wheeler & Treisman, 2002)

How do we update visual working memory? When modifying our memory of an object to integrate new information with stored information, do we use an object-based process or a feature-based process? Previous work has suggested that updating is not object-based, but rather feature-selective, because people selectively update one feature of a memorized object without refreshing the memory of other features of the object (Ko & Seiffert, 2009 Mem Cognit). To test whether updating shows any object-based benefit, we asked participants to update two features of their visual working memory of either one object or two objects. Participants memorized a display composed of three colored, oriented bars in three different locations. The display was followed by a cue instructing participants to update their memory of one feature of the object at the same location as the cue. To manipulate whether one or two objects were updated, a second cue either appeared at the same or different bar location as the first cue. Also, the two cues were either the same feature or different features. After the cues, a single bar probe appeared at one of the three bar locations. Participants indicated whether the probe matched their memory. The facilitation effect of updating features did not spread to the other feature of the cued object or features of other objects, for both one object (interaction F(1,24)=21.9, p<.001) and two-object (interaction F(1,24)=7.35, p<.013) updating. This was consistent with previous results showing feature-selective mechanism in updating. However, when the updated object was probed, participants performed more accurately when updating one object than two objects (F(1,24)=29.7, p<.001), showing evidence for an object-based mechanism. In addition, the feature-selective facilitation effect was significantly larger in one object updating than two-object updating (F(1,24)=6.30, p<.02). Taken together, these results suggested that updating relies on both object-based and feature-selective mechanisms.

Related Publications: Ko, P. C. & Seiffert, A. E. (2009). Updating objects in visual short-term memory is feature-selective. Memory and Cognition, 37(6), 909 - 923. [ link ]

Park, H., & Seiffert, A. E. (2012). Updating visual working memory is both object-based and feature-selective. Journal of Vision, 12(??), 442. [ link ]

[ top ]