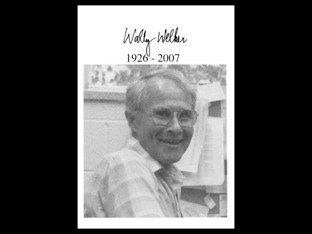

On the other hand, right across the hall from me where I had my lab, was Wally Welker. Wally Welker had come as a postdoc to the department and retained as a faculty member - same thing happened to me. They had a lot of postdocs but didn’t retain many, maybe just the ones that couldn’t get jobs. [laughter]

I became an assistant professor.

Wally Welker had a great deal of daring, and what he did, he started recording from his animals with microelectrodes and demonstrating how superior this method was for somatosensory cortex. He also did a lot of somatosensory cortex mapping – I’ll show you one of his results in a few minutes. At the same time he had the foresight to think that all the brains going through the laboratory should be processed in a standard way and keep standard records of the animal’s sex and so on, and build up a brain collection – which now I believe has reached 117 species. And now that is a great resource for present-day scientists. He died recently, and there is going to be a memorial service symposium in Washington, DC, June 25-27 at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, a Division of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology where the Wisconsin brain collections is now kept.

Conference web site with list of participants

Welker was very interested in comparative studies, and for example, he lived with some gibbons for a while – they just ran around in his apartment – that’s when one of his wives left him – [laughter]. And then he had a house at another time – he raised a lion from a little cub to an adult, and it just ran around loose. And when it was about this big it was sort of cute and if you would run, it would run and knock you down, but it didn’t eat you [laughter]. But later it disappeared – I think the neighbors complained – they didn’t want a lion running around in their neighborhood. But that was his curiosity.